Queen’s Gambit

- July 31, 2021

- by

- Rachel

Nobody wants to be a victim these days. Victims tend to be dead or incapacitated in a fundamental way that does not fit US cultural values of independence and strength. I am no exception. Part of the reason I started this blog was to face my fears, my shame, and let the light break the cycles that would otherwise entrap me.

“Victim” is a charged word. A 2020 article in Time pointed out the complexities surrounding the term, noting that the tendency is to prefer the word “survivor.” We like that word, because it connotates being alive, having some power and control. As the author, Kate Harding, points out, the origin of the word victim does not signify anything other than someone who had a bad experience that was not in any way deserved. Nevertheless, in contemporary parlance, the term victim became a negative, pushing us to self-designate as survivors.

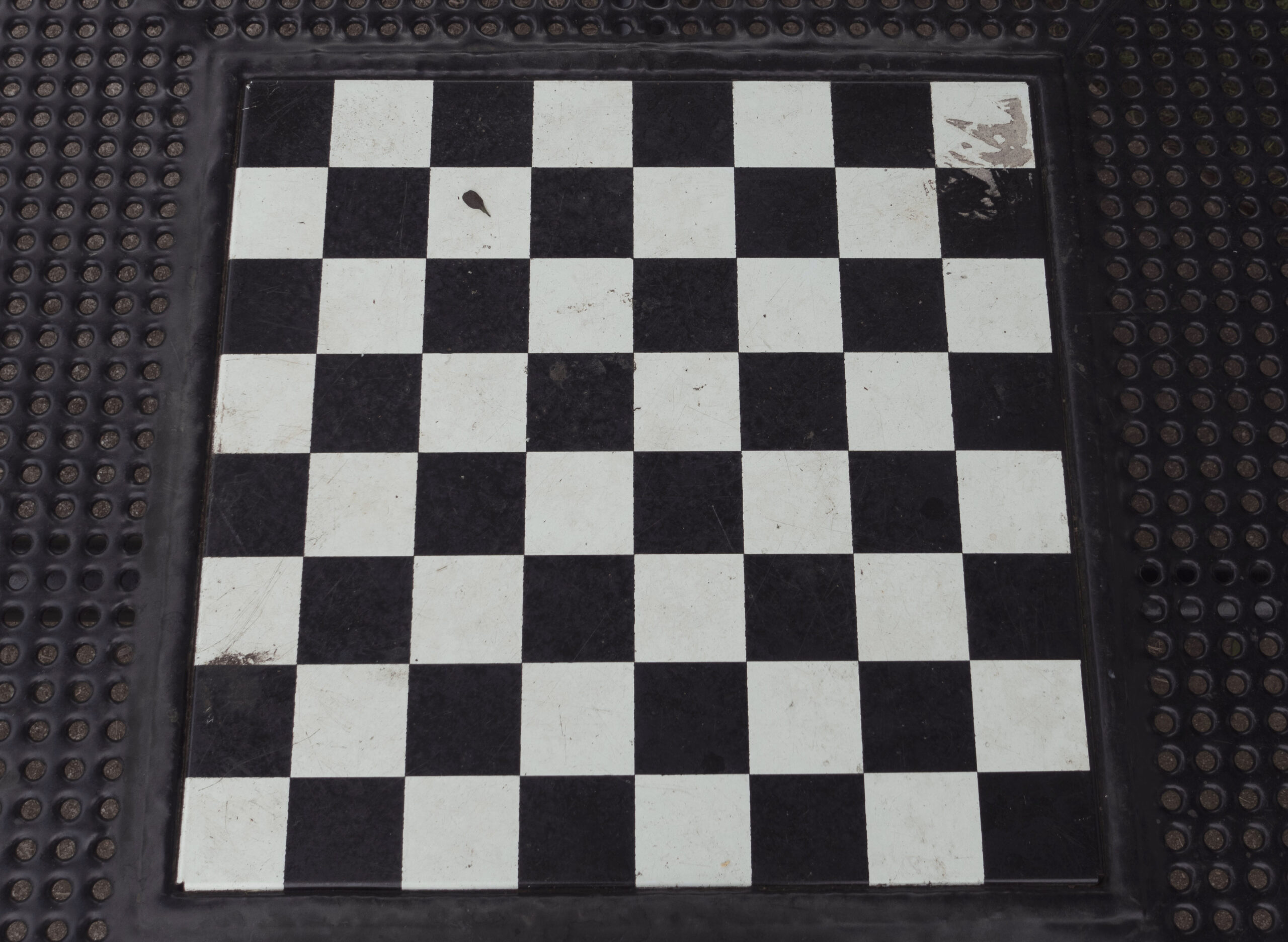

Being both survivors of sexual assault, my relationship with CP (from friendship to relationship to co-parenting) has had to deal with questions of victimhood in serious ways. Early on, we would get in horrible fights which, in retrospect, we now know were due to unconscious triggers that we had not yet learned to identify as such. Although emotions would run high, the fights would play out in a surprisingly systematic fashion, like two chess players facing each other across the board. Attack. Defend. We would find ourselves locked in a vicious spiral where neither of us was acting as a rational adult. Instead, our child selves would glare at each other across the living room, brandishing any verbal weapon available from the arsenal in order to inflict maximum emotional damage.

When we reached the point where both were so triggered that every single instinct we had honed to survive our childhoods was on alert, and our minds were bent on self-preservation at any cost, someone’s voice would run cold, their eyes narrow and they would throw down, “Stop being a victim.” Checkmate. By throwing out the word “victim,” you won, guaranteeing your own safety at the expense of the other person you claimed to love and, ultimately, to the detriment of your relationship.

Despite preferring to call myself a survivor, before becoming one, I was a victim. No wording can change that. I was a victim for years. Until I made my peace with this, before I consciously explored what it meant psychologically to have been a victim for so long, I repeatedly engaged in destructive patterns that meant I would be a victimized again.

One particular pattern took me through multiple relationships, each ripping my heart to pieces as I stood in its wake, alone, exhausted and sobbing. That was the pattern of learned helplessness. One of the classic psychological studies on trauma that explains this concept came from research in the 1970s by a man named Martin E.P. Seligman. While animal experimentation makes my blood run cold, his studies established the connection between resilience to trauma and questions of control. What he discovered is that dogs who were repeatedly subjected to traumatic situations without being given an option to escape, gave up to the point where, even when a way of escape was eventually offered, they were incapable of taking the way out. Although later studies have nuanced these findings, there are some key components to learned helplessness that particularly apply to those of us who survived childhood abuse.

We are all aware of what is like to be helpless, to have a complete inability to control one’s circumstances. Babies are helpless, for example. Studies have shown that evolutionarily, we are neurologically wired to see babies as adorable, to have a surge of desire to protect and care for them. That’s what helps the species survive. Children continue to be mainly dependent on their caregivers as they grow, asking for their needs to be met the best way they know how, aware that they depend on their caregivers for survival. The psychologist Ross Buck discovered that children whose caregivers ignore or punish them when they ask for a need to be met tend to shut down. This does not mean they stop needing or feeling stress. It merely means they stop expressing their needs, knowing they will not be met anyway. The consequences of this are long-lasting, similar to what was found in the studies with the dogs.

When a child is repeatedly subjected to abuse or neglect, they shut down. The stress remains the same, but they cease to request assistance. Not only that, but they can get to the point where they become so accustomed to being helpless, they are not capable of seeing anything else. This mechanism, when it persists into adulthood, can lead to an ongoing state of learned helplessness which Gabor Maté defines in his book, When the Body Says No, as “a psychological state in which subjects do not extricate themselves from stressful situations even when they have the physical opportunity to do so.”

In my case, as a result of living my childhood in a situation where any type of independence was deemed rebellious, where God was interpreted through the lens of patriarchy and authoritarianism, where ongoing sexual assaults could not be addressed for fear of the consequences, I learned that when it came to control over my body or over important life decisions, I was helpless. This lingered for years. It covered everything from choosing a career—because there was so much pressure to not make a mistake and choose the “wrong” one—to relationships where the other person defined who I was, where my needs were secondary because I did not realize I could say “no” without paying the price. My first serious relationship told me flat out that we had to have sex regardless of my feelings on the matter, because it was the only way he could express how he loved me. No sex meant no relationship. Naturally, I complied, because deep down I did not believe I had any other options.

Looking back, I often felt trapped against a wall when there was a door wide open to the side. I could not see it. I kept playing the same opening gambit, and I kept being checkmated. Staring at yet another loss, I would ask myself why I had to suffer so much, why I kept being in so much pain. It took years of therapy before I realized that the only way to avoid the loss was to stop playing that gambit, to learn a new strategy. I wasn’t helpless. I just felt helpless. I had to learn to see my other options.

I’m not the only one who keeps playing the same opening and hoping for a better outcome. There is no blame in this, because we are unconsciously pulled to the familiar, to the same gambits. Until we become conscious. Until we take steps to learn a new way of functioning that breaks the cycle.